Around the world, an exciting new generation of greenfield airport projects are currently in the pipeline. Beijing is building a gigantic second international hub at Daxing, planned by NACO and designed by ADPI in collaboration with Zaha Hadid. On the shores of the Black Sea, Istanbul is constructing a third airport on an even grander scale. And down under in Sydney, plans are afoot to design a new hub from scratch on the city’s western outskirts.

Greenfield Airports and Urban Growth:

What Drives Success?

-

-

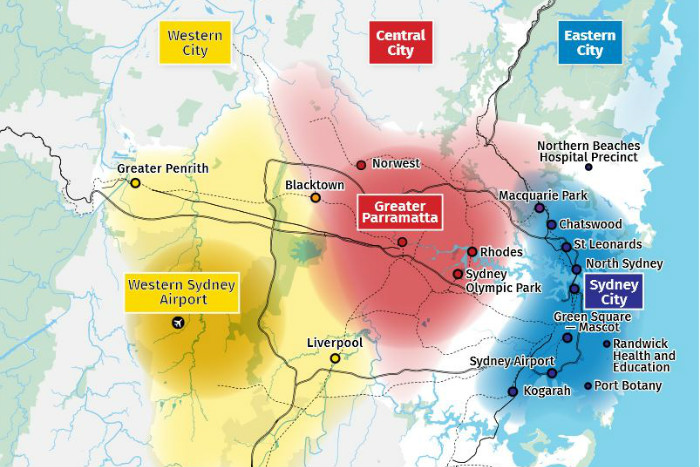

All of these projects are being built with two goals in mind. On the one hand, they aim to increase capacity in dynamic aviation markets where passenger and cargo volumes are set to grow for the foreseeable future. At the same time, these greenfield projects double as a strategy for large-scale urban development on the ground. Beijing, Istanbul, and Sydney have all experience rapid population growth over the last few decades. Building major infrastructure projects like a greenfield airport is one way to expand these cities’ footprint beyond current boundaries and, in so doing, to relieve pressure on the historical city center. From the perspective of local and national governments, these airport projects are as much about increasing aerial connectivity as they are about creating jobs and educational opportunities in underdeveloped parts of the urban region. In Beijing, Daxing is just one of many satellite cities being built on the periphery of the Chinese capital. In Sydney, the new airport will form the core of the so-called Western City, and will serve as a structuring device for the Australian metropolis’s next major wave of urban growth.

-

With thoughtful planning, these two goals—increasing air capacity and expanding the city—can be complementary. But cities like Beijing, Istanbul, and Sydney also run the risk of making big mistakes early on in the design process that can lead to enormous social, financial, and environmental costs further down the line. At best, these greenfield projects will generate vibrant new airport hubs and will bring jobs, services, and amenities to poorer and peripheral parts of the urban region. At worst, they risk becoming white elephants: isolated on the urban fringe, unpopular among airlines and their customers, and eating up vast sums of public and private money that could have been better spent elsewhere. Tokyo Narita and Montréal Mirabel serve as cautionary tales, and as negative examples that no one wants to repeat.

Planning a successful greenfield airport—one that effectively manages traffic in the air and stimulates urban development on the ground—requires a deep understanding of both the global aviation industry and the local urban context. But whether you’re planning a new airport in Australia, China, or Turkey, the success of these projects boils down to a discrete set of issues. Below, I’ve outlined five critical drivers that fundamentally determine the success or failure of a greenfield airport:

-

Governance

Given the scale of development, greenfield projects tend to cut across various geographic and administrative boundaries: towns and provinces on the one hand, and government ministries and regional planning authorities on the other. The more actors that are involved, the harder it becomes to implement a coherent long-term growth strategy for the airport and the surrounding communities. That’s why it’s crucial to establish a supra-jurisdictional governing body for the airport area: one that brings all stakeholders to the table, and that creates a forum where binding agreements can be negotiated and enforced. If not, your future planning strategies will become bogged down by local politics and torpedoed by individual interests.Successful airports like Amsterdam Schiphol have developed coordinating bodies that moderate a productive dialogue between public- and private-sector stakeholders. Dedicated airport-area institutions enable airports to identify synergistic development strategies, and to avoid the protracted lawsuits and institutional paralysis that plague their less successful peers.

-

Competition

Existing airports in the same catchment area will inevitably have an advantage over an upstart airfield. Chances are that these older airports will be located much closer to major population centers, and will therefore be more popular among passengers and businesses. And unless there are serious problems at the old airport, airlines will prefer to stay where they are rather than move house.On the financing front, private investors tends to shy away from the risks inherent in any greenfield project, favoring established airports with a proven track record of operational transparency and reliable returns on investment. (See an article on that here.) How can greenfield airports encourage pax, airlines, and businesses to relocate to a much more distant location, and how can they demonstrate the new airport’s viability to skeptical investors?

One approach is to force the existing airport to close—although I doubt that creating a monopoly will serve you well in the long run. Barring that, greenfield hubs need to consider a range of financial, practical, and qualitative incentives that will draw customers to a distant and untested site. Will the new airport offer tailored amenities for specific pax types? A more attractive pricing structure for airlines? Better housing and services for employees of airport-area businesses? All of these options need to be considered from day one.

-

Accessibility

Greenfield airports tend to be built very far from the CBD. That distance gives operators a lot of flexibility—no curfews, no encroaching developments—but it also makes it difficult to attract customers. The most successful greenfield airports tackle this challenge from the get-go by planning a variety of ground access options that vary by price and speed. In so doing, greenfield airports can appeal to both busy professionals (who prioritize time over money, and prefer a reliable high-speed access mode) and to commuters and leisure customers whose main concern is cost. When one system fails—a traffic jam on the motorway, or a signal failure at a railroad junction—travelers can quickly turn to alternatives.The takeaway: leading greenfield airport projects—I’m looking at you, Hong Kong—incorporate a wide range of ground access options: expressway, high-speed rail, metro, ferry, and helicopter. Relying on a single transport mode is a recipe for disaster.

-

A clear brand identity

As aviation markets mature, they often develop into multiple-airport regions (MARs) where two or more airports serve the same catchment area. MARs work best when each airport has a clear understanding of its purpose in relation to other airports in the region, and is able to communicate that mission to its customers with a clear brand identity. Will the greenfield airport specialize in long-haul service? Low-cost flights? Cargo services? Particular geographic markets, such as Asia or the Middle East? Will the airport have one or more home carriers, and will the adjacent airport city have a reliable anchor tenant? (Answer: it better!) Will it be a hub for a specific airline alliance like OneWorld or SkyTeam? Above all, how will your greenfield project differentiate itself from existing airports? If your only answer is “location,” then you’re in for a bumpy ride.As the urban planning expert Robert Freestone pointed out in a recent article, current greenfield projects in Sydney (and in Beijing, I might add) have yet to communicate a clear identity to the flying public. Establishing that identity early on in the planning process is crucial for the successful launch of these projects, and to ensure their long-term viability.

-

Integrate the airport into the city

No greenfield site is truly a blank slate. In order to design successful large-scale urban developments that are based on accurate demand forecasts, it’s extremely important to be aware of the social, cultural, economic, and environmental dynamics of the urban region surrounding the new airport. What industries are already located there, and how could potential synergies with the airport be incorporated into future plans? What kinds of businesses, services, and amenities are currently missing from that part of the city, and how could the urban districts being built around the airport productively engage with those unmet demands? On the jobs front, do local workers have the skills that the future airport will need? If not, how can new employees be enticed to the region, and how can current residents be brought up to speed?Lastly, how will ecological issues like water management and urban food security factor into future development plans, and to what extent will they alternately constrain growth or open up new models of urban design? As Sydney’s environment commissioner Roderick Simpson pointed out in a recent talk sponsored by Urbis, these are questions that any serious airport-area developers need to be asking themselves.

The takeaway: successful greenfield projects need to be attractive not only to passengers and airlines, but also to local businesses and residents: as a place to work, as a place of recreation and consumption, and also—at a generous distance—as a place to live.

-

Planning for Success

It’s crucial to consider these five drivers of success before a single master plan has been drafted, and before a single tender has been issued. Discussing these issues is also the first step towards articulating a compelling vision of what the new airport aims to achieve, and for communicating that vision to investors and the public at large. Apart from a few industry wonks, very few people can relate to technocratic concepts like the “aerotropolis” and “airport city.” How can the future airport craft a story that allows everyday folks to connect with the greenfield project’s broader goals, and to become enthusiastic about its potential to bring vitality to underdeveloped parts of the region?Simply put—how can a new airport communicate a vision that will convince a passenger, an airline, a business owner, or a local resident to trek dozens of kilometers to the very edge of the city? And how can that vision be broadcast through media, exhibitions, public events, and word of mouth?

That’s the multi-billion dollar question.

Because ultimately, communicating that vision, and identifying the steps needed to realize it, is the biggest challenge for greenfield airport projects all over the world.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-