How do successful cities build a new airport

— and redevelop the old one?

-

-

by Max Hirsh

Around the world, airports are launching ambitious expansion programs: adding new terminals and runways to meet future demand. But what happens if the airport can’t be expanded—either due to flight restrictions, or because there simply isn’t any room to grow?

That’s the challenge facing older inner-city airfields, many of which are being replaced by new hubs located far from the urban core. These relocation projects aim to enable 24-hour operations, reduce friction with the airport’s neighbors, and provide flexibility for future expansion.

Closing an old airport and replacing it with a new one is no small feat. Currently, cities like Lisbon, Riyadh, and Warsaw are grappling with this unique challenge. Berlin and Istanbul have recently launched new hubs, but haven’t yet redeveloped the former airfield. Still others like Nairobi and Reykjavík are mulling such moves, but haven’t yet pulled the trigger.

In all these cities, decision makers face the same challenge: how can we build a new airport, and how can we redevelop the old one?

-

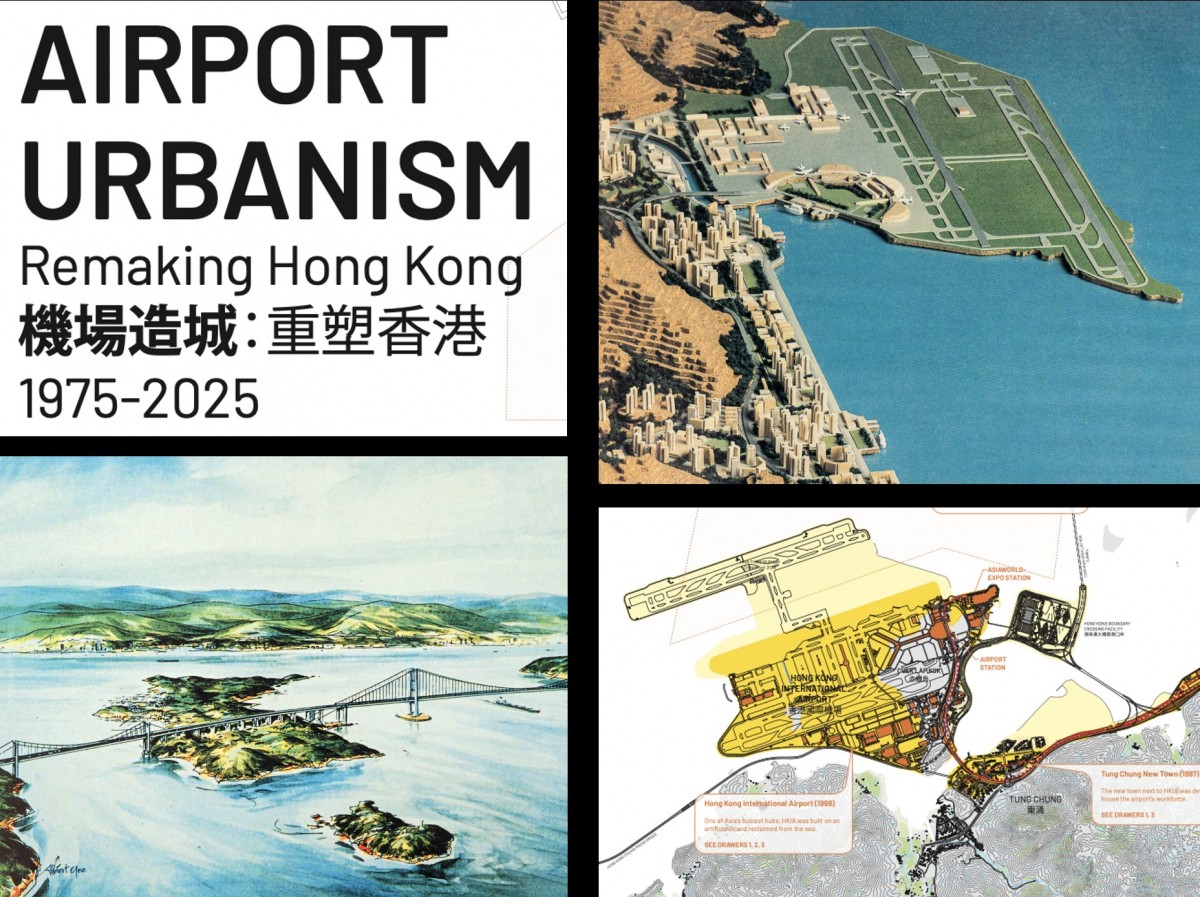

That’s the question Dorothy Tang and I ask in our exhibition at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. Focusing on Hong Kong International Airport—which opened in 1998—we investigate how successful cities can learn from Hong Kong in order to harness the transformative power of airport urbanism.

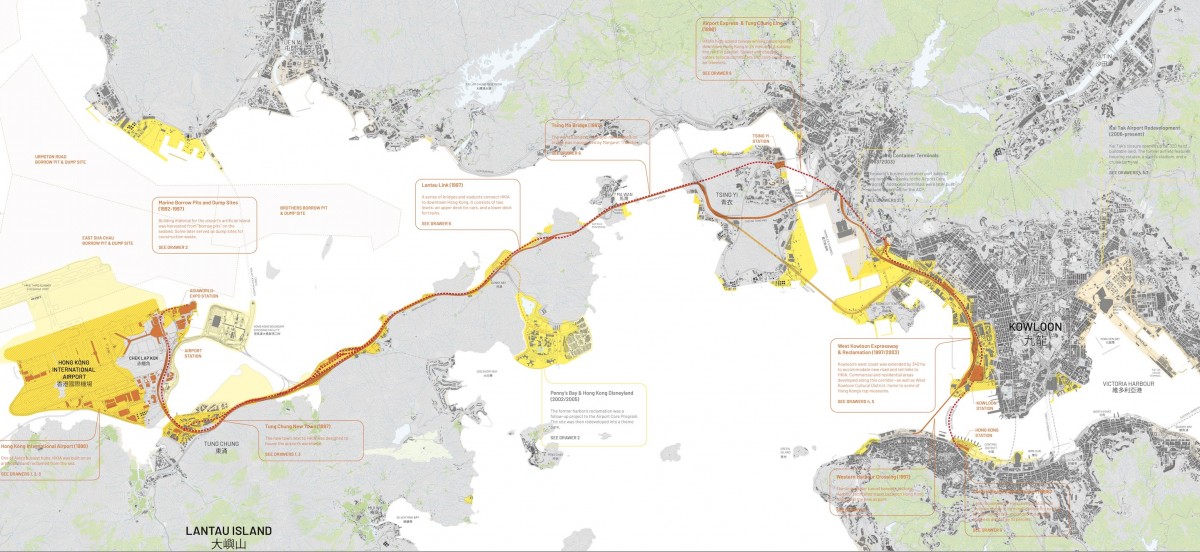

2025 marks the 50-year anniversary of that transformation, which began with the site selection for the new airport and culminated with the recent edevelopment of the former airfield. As this timeline suggests, building a replacement airport doesn’t happen overnight. Complex planning, land acquisition, and consultation processes can stretch on for years or even decades—leading to bitter fights between the airport’s advocates and opponents. Poorly executed projects can end in failure: with the examples of Mexico City, Montréal, and Nantes serving as powerful cautionary tales.

We prefer to focus on what works, rather than what doesn’t. With that in mind, our exhibition investigates two key questions that drive success: first, how will people travel to the new airport? And second, what will happen to the old one?

-

How will we travel to the new airport?

The term “ground access” describes the surface transportation that passengers and staff use to travel to and from the airport. Typical examples include private cars, taxis, buses, and trains. For a greenfield hub far from the city, ground access is a crucial consideration. It’s also one that’s easily overlooked.

Many customers respond negatively when they hear that a new airport is being built in a distant location. Passengers complain about the extra time (and money) needed to get there. Airlines worry that lengthy commutes will impact their ability to recruit staff. Business leaders fear a loss in competitiveness compared to more convenient hubs.

Lastly, let’s not forget that ground access is the second largest source of airport emissions. A greenfield hub without good transport links will find it hard to reduce its carbon footprint. That can spook investors and policy makers.

-

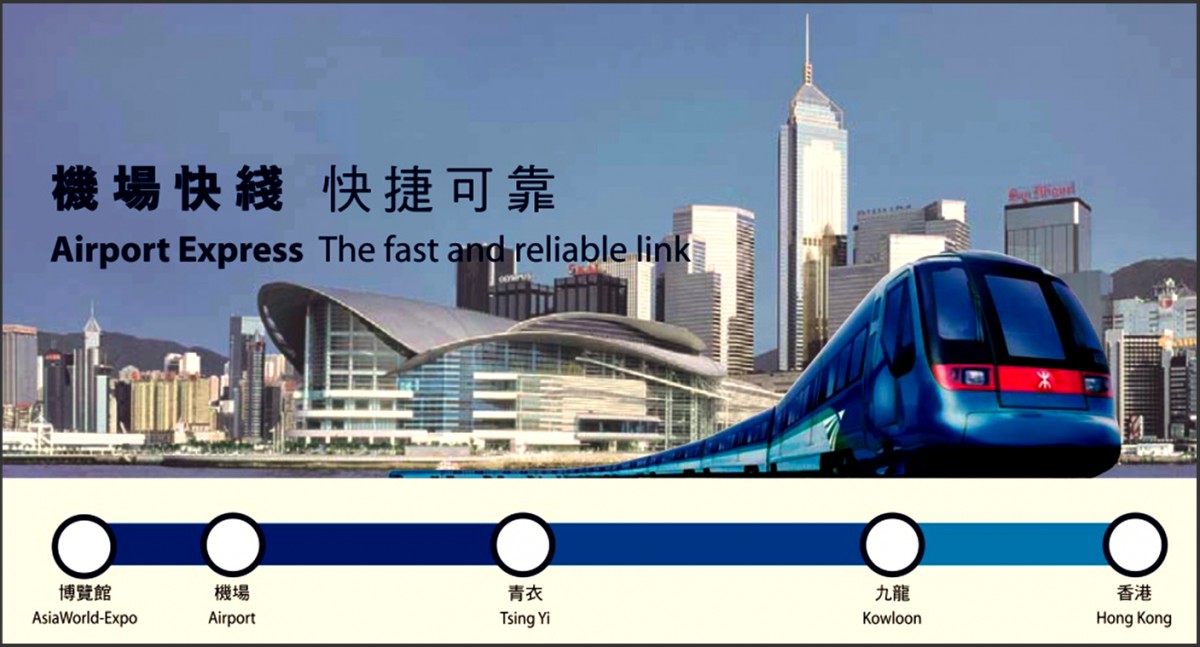

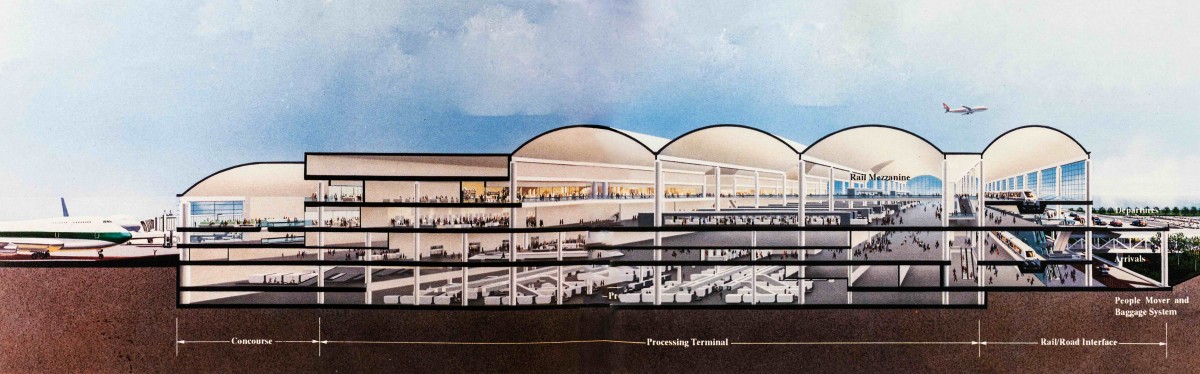

HKIA’s planners tackled these challenges head-on. From Day 1, they introduced a high-speed train that connects the terminal to downtown Hong Kong in less than 30 minutes. Arriving passengers can walk off the plane, collect their luggage, hop on the Airport Express train, and jump in a taxi or subway to their final destination – all without a single change in level, and with a luggage cart waiting every step of the way.

-

Airport Express is part of a 35km corridor that links HKIA to the inner city, offering various ground access options that differ by price and speed. Budget travelers favor a local subway line, which is slower and cheaper than its high-speed cousin. Express coaches connect the airport to all of the city’s 19 districts. Employee buses provide affordable 24-hour access to HKIA—a big plus for shift workers.

-

In addition to connecting HKIA, the airport corridor paved the way for decades of transit-oriented development. Subway stations along the corridor triggered new residential and industrial estates in the suburbs. Downtown, mixed-use districts emerged around two Airport Express terminals. Studded with offices, hotels, malls, apartments, and museums, these new precincts increased the surface area of Hong Kong’s CBD by more than 10 percent.

The takeaway? Hong Kong’s ground access strategy required close coordination between the airport, urban planners, and local transport authorities. It also involved heaps of cash. These conditions might be tough to replicate, but HKIA’s approach highlight two key success drivers.

-

First, new road and rail links are a great way to promote the new airport and allay fears about its distant location. They’re also an excellent tool to stimulate urban development. That can help build support among key decision makers: who will be more willing to support the new hub if it contributes to local development priorities like housing and public transport.

Last but not least, convenient ground access raises the market value of the airport’s land assets. In fact, it’s one of the key drivers of airport real estate development.

-

What will happen to the old airport?

When an airport is decommissioned, it leaves behind a vast amount of land, buildings, and infrastructure, representing decades of investment. These assets are crucial for the airfield’s redevelopment. How do successful cities do that?

The first question is whether the site will continue to function as an airport. Some global cities—e.g. Bangkok, London, LA—can easily support more than one hub. (This is what transport nerds like myself call a multi-airport system.) In smaller markets, the airport might operate on a reduced footprint, serving niche demographics such as private jets or military flights.

Most cities, however, prefer a clean break. Keeping the old airport open can make it harder to attract customers to the new hub. For airlines, maintaining two bases is complex and costly. And from an urban development perspective, closing the airport offers a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to build entire new districts from scratch.

-

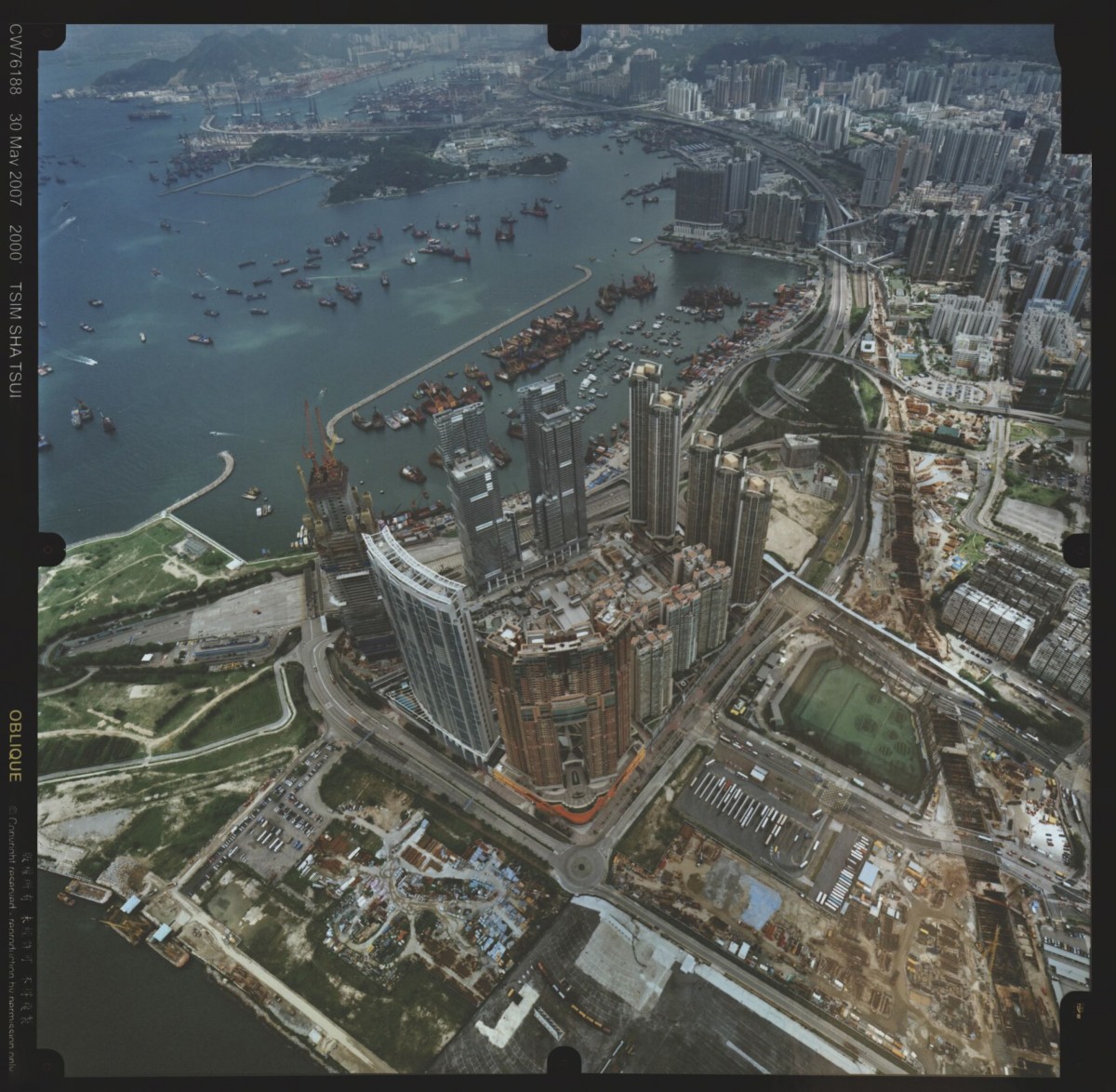

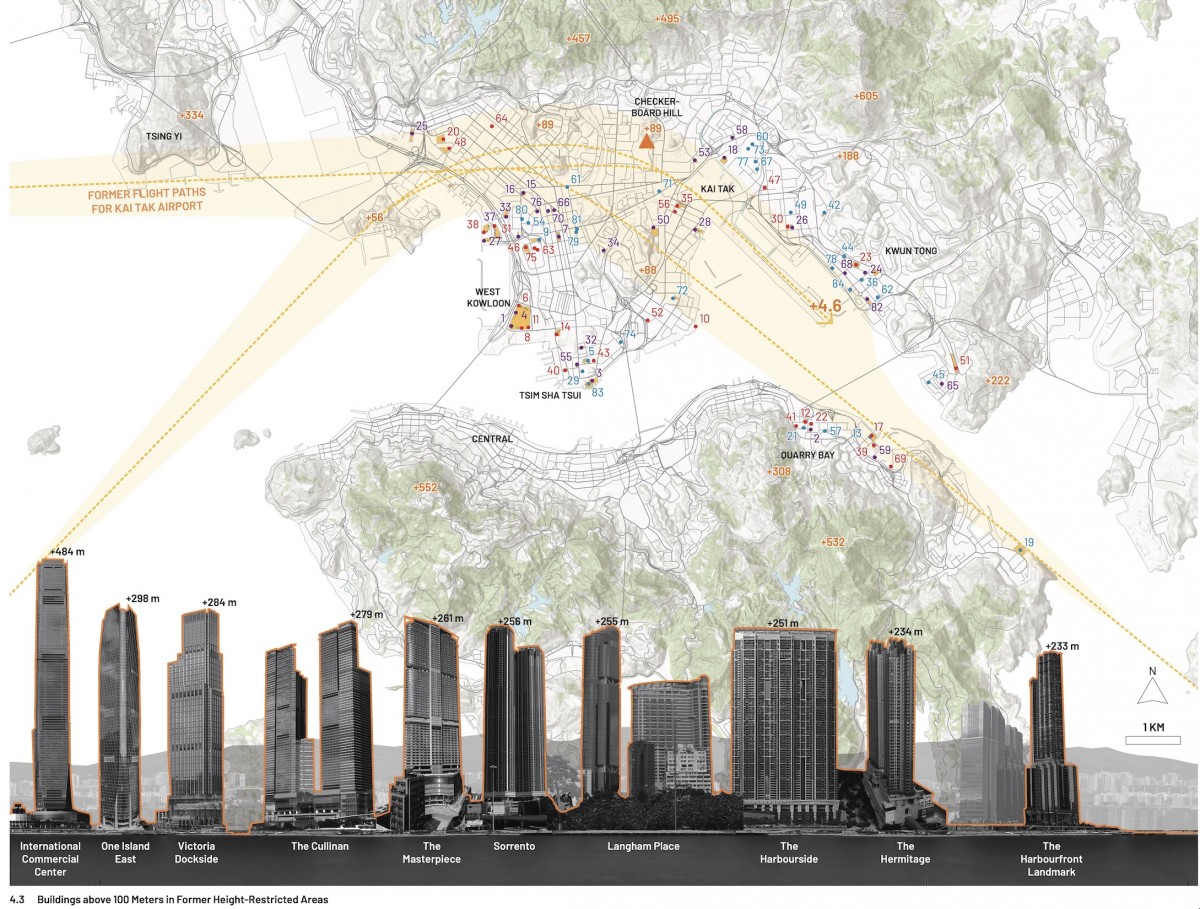

That was the case in Hong Kong, where the opening of HKIA coincided with the closure of the former airfield at Kai Tak. For decades, aircraft-related height restrictions constrained development across the inner city. This was particularly apparent in Kowloon's busy commercial areas, where building heights were capped. The relaxation of those restrictions after 1998—up to a maximum of 530m—launched a new generation of super-tall skyscrapers.

-

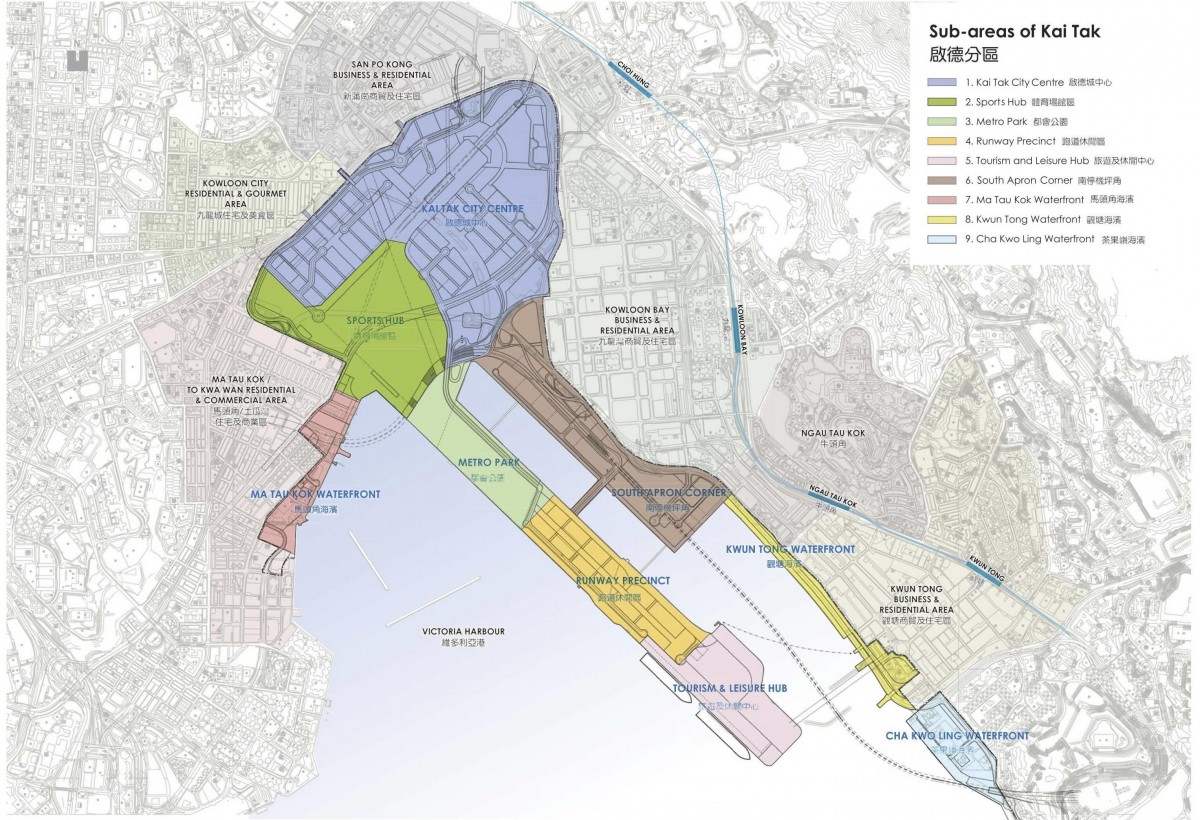

Kai Tak’s closure released millions of square meters of airspace across the inner city. It also opened up 320ha of land at the airport itself, which was converted into 9 mixed-use districts with 86,000 residents. The apron was redeveloped into housing estates and a sports stadium; while the runway was converted into a cruise terminal, more housing, and a park.

The takeaway? Transferring airport operations from one site to another is extremely complex. For a new hub, construction delays and technical glitches are inevitable during the start-up phase. Many cities opt for a transition period, phasing out the old airport while the new hub comes online. Problems arise when it’s unclear how long that “transition” will last: a few weeks, months, years? With each day that question remains unanswered, it becomes less likely that the old airport will actually close.

That may be fine in markets where traffic is growing faster than forecast, or where the new airport is taking longer to complete than expected (i.e., every new airport ever). In those cases, maintaining the old airfield can relieve operational pressure and compensate for the new hub’s growing pains.

-

The tougher question is what happens next. Consider Berlin, which closed Tempelhof airport in 2008. The site covers 355ha of valuable inner-city land—for comparison, that’s roughly the same size as downtown Frankfurt. It also has three subway stations and two highway exits. Yet due to local political debates that are far too tedious to reprint here, Tempelhof remains largely as it was when it closed 17 years ago. Apart from a lovely community garden and some food trucks, the former airfield is a massive windswept wildnerness, smack-dab in the middle of a city suffering from an acute housing crisis.

-

The contrasting examples of Berlin and Hong Kong point to three success factors for any airport redevelopment project.

The first is to create a compelling vision that links the airfield’s transformation to the city’s future development goals. That could mean building affordable housing, work spaces for new industries, attractive recreational areas—or all of the above.

The second success factor? Establish a development authority that has both the capacity and resources to achieve that vision—and actively seeks out strategic partners. Airfields are very large sites. To redevelop at this scale, it’s essential for public and private partners to work well together.

The final success factor is to focus on early wins. Redeveloping an airfield takes time, and there will be many different views on what that process should look like. Too often, these debates get bogged down by local politics and individual interests. That’s why it’s critical to kick-off with projects where consensus prevails, and to build trust among key partners in order to lay the groundwork for future development phases.

-

Final thought

Hong Kong’s new airport launched a paradigm shift in the spatial organization of the city: what we might call airport urbanism. Our exhibition investigates how planners, designers, and developers transformed Hong Kong into a global aviation hub—while also creating new spaces to live, work, and play. In so doing, we hope to inspire other cities who are at the start of that exciting journey.

Airport Urbanism: Remaking Hong Kong will be exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale until 23 November 2025.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-